As the world awaits vaccines to bring the COVID-19 pandemic under control, UC San Francisco scientists have devised a novel approach to halting the spread of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes the disease.

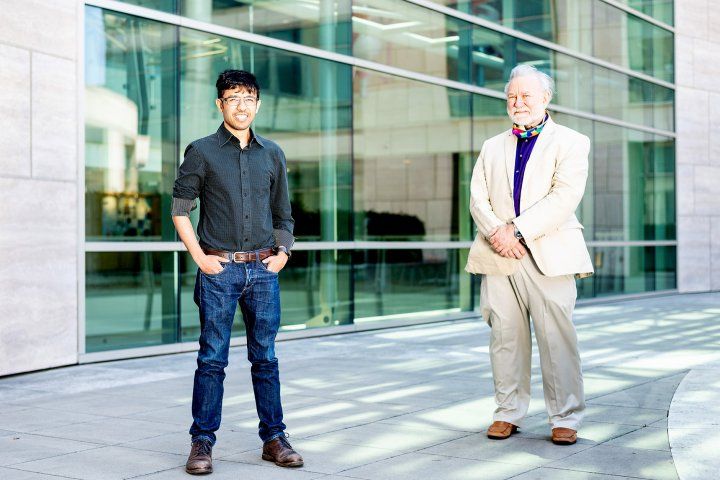

Led by UCSF graduate student Michael Schoof, a team of researchers engineered a completely synthetic, production-ready molecule that straitjackets the crucial SARS-CoV-2 machinery that allows the virus to infect our cells. As reported in a new paper, now available on the preprint server bioRxiv, experiments using live virus show that the molecule is among the most potent SARS-CoV-2 antivirals yet discovered.

In an aerosol formulation they tested, dubbed “AeroNabs” by the researchers, these molecules could be self-administered with a nasal spray or inhaler. Used once a day, AeroNabs could provide powerful, reliable protection against SARS-CoV-2 until a vaccine becomes available. The research team is in active discussions with commercial partners to ramp up manufacturing and clinical testing of AeroNabs. If these tests are successful, the scientists aim to make AeroNabs widely available as an inexpensive, over-the-counter medication to prevent and treat COVID-19.

“Far more effective than wearable forms of personal protective equipment, we think of AeroNabs as a molecular form of PPE that could serve as an important stopgap until vaccines provide a more permanent solution to COVID-19,” said AeroNabs co-inventor Peter Walter, PhD, professor of biochemistry and biophysics at UCSF and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator. For those who cannot access or don’t respond to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, Walter added, AeroNabs could be a more permanent line of defense against COVID-19.

“We assembled an incredible group of talented biochemists, cell biologists, virologists and structural biologists to get the project from start to finish in only a few months,” said Schoof, a member of the Walter lab and an AeroNabs co-inventor.

Llama-Inspired Design

Though engineered entirely in the lab, AeroNabs were inspired by nanobodies, antibody-like immune proteins that naturally occur in llamas, camels and related animals. Since their discovery in a Belgian lab in the late 1980s, the distinctive properties of nanobodies have intrigued scientists worldwide.

“Though they function much like the antibodies found in the human immune system, nanobodies offer a number of unique advantages for effective therapeutics against SARS-CoV-2,” explained co-inventor Aashish Manglik, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of pharmaceutical chemistry who frequently employs nanobodies as a tool in his research on the structure and function of proteins that send and receive signals across the cell’s membrane.

For example, nanobodies are an order of magnitude smaller than human antibodies, which makes them easier to manipulate and modify in the lab. Their small size and relatively simple structure also makes them significantly more stable than the antibodies of other mammals. Plus, unlike human antibodies, nanobodies can be easily and inexpensively mass-produced: scientists insert the genes that contain the molecular blueprints to build nanobodies into E. coli or yeast, and transform these microbes into high-output nanobody factories. The same method has been used safely for decades to mass-produce insulin.

But as Manglik noted, “nanobodies were just the starting point for us. Though appealing on their own, we thought we could improve upon them through protein engineering. This eventually led to the development of AeroNabs.”

Spike Is the Key to Infection

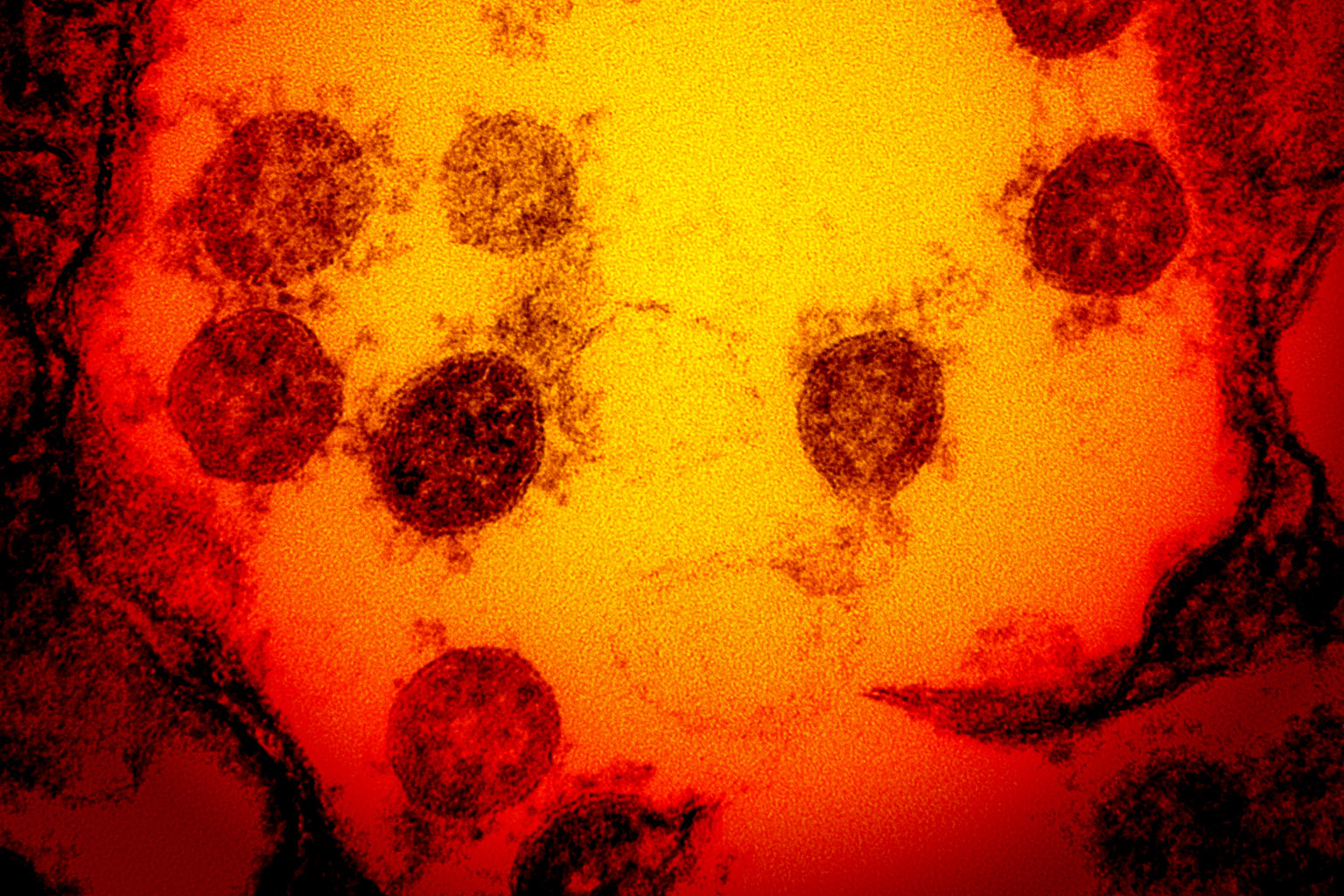

SARS-CoV-2 relies on its so-called spike proteins to infect cells. These spikes stud the surface of the virus and impart a crown-like appearance when viewed through an electron microscope – hence the name “coronavirus” for the viral family that includes SARS-CoV-2. Spikes, however, are more than a mere decoration – they are the essential key that allows the virus to enter our cells.

Like a retractable tool, spikes can switch from a closed, inactive state to an open, active state. When any of a virus particle’s approximately 25 spikes become active, that spike’s three “receptor-binding domains,” or RBDs, become exposed and are primed to attach to ACE2 (pronounced “ace two”), a receptor found on human cells that line the lung and airway.

Through a lock-and-key-like interaction between an ACE2 receptor and a spike RBD, the virus gains entry into the cell, where it then transforms its new host into a coronavirus manufacturer. The researchers believed that if they could find nanobodies that impede spike-ACE2 interactions, they could prevent the virus from infecting cells.

Nanobodies Disable Spikes and Prevent Infection

To find effective candidates, the scientists parsed a recently developed library in Manglik’s lab of over 2 billion synthetic nanobodies. After successive rounds of testing, during which they imposed increasingly stringent criteria to eliminate weak or ineffective candidates, the scientists ended up with 21 nanobodies that prevented a modified form of spike from interacting with ACE2.

Further experiments, including the use of cryo-electron microscopy to visualize the nanobody-spike interface, showed that the most potent nanobodies blocked spike-ACE2 interactions by strongly attaching themselves directly to the spike RBDs. These nanobodies function a bit like a sheath that covers the RBD “key” and prevents it from being inserted into an ACE2 “lock.”

With these findings in hand, the researchers still needed to demonstrate that these nanobodies could prevent the real virus from infecting cells. Veronica Rezelj, PhD, a virologist in the lab of Marco Vignuzzi, PhD, at Institut Pasteur in Paris, tested the three most promising nanobodies against live SARS-CoV-2, and found the nanobodies to be extraordinarily potent, preventing infection even at extremely low doses.

The most potent of these nanobodies, however, not only acts as a sheath over RBDs, but also like a molecular mousetrap, clamping down on spike in its closed, inactive state, which adds an additional layer of protection against the spike–ACE2 interactions that lead to infection.